I found out that some people are still confused about what Node.js is. For many it is just “JavaScript on the server”. In fact, while they primarily see JavaScript and focus on this, they overlook the most important part of Node.js: the event driven model.

So, what’s Node ?

The Node.js website reads:

Node.js is a platform built on Chrome’s JavaScript runtime for easily building fast, scalable network applications. Node.js uses an event-driven, non-blocking I/O model that makes it lightweight and efficient, perfect for data-intensive real-time applications that run across distributed devices.

Well, it says it all ! Node is a server-side JavaScript Runtime Environment built from the ground-up to be 100% non-blocking. It uses V8, the Google Chrome’s JavaScript engine, as the JavaScript interpreter at its core and complements it with a complete non-blocking API, based on an asynchronous I/O model. On top of this API, Node provides a set of modules to build network-enabled applications.

However, Node is not the first attempt to build a server-side JavaScript solution. What makes Node different is that it is in fact really more than just JavaScript on the server. Again, JavaScript is not the most important part of Node, it is just a mean to achieve what really matters: a non-blocking event-driven platform. There is much more to Node than just JavaScript. If you come from a “traditional” background in backend development in C/C++, Java, etc… then you will have to rewire your brain and start thinking “asynchronous”. This is where the power of Node truly is. And with Node thinking asynchronous is simpler.

Why does it matter ?

Anyone who has been involved in building large scale applications knows that scalability and performance are what matters the most. Usually one wants to scale out rather than scaling up. That is to say, it is better to scale by adding more machines rather than bigger machines. However, it is still needed to make the most out of a machine and to have it serve seamlessly as many clients as possible in parallel. This is a matter of costs (after all, it is always a matter of costs ). A server will therefore need to serve concurrently many requests. Concurrency is really what matters.

The traditional concurrency model

The traditional answer to this problem is to spawn a new child process to serve each connection. The parent process will remain available for listening to new connections. Each new connection results in the creation of a child process dedicated to it. Another alternative is to use threads. In multithreaded servers each connection gets a dedicated thread to be served while the main thread keeps listening to incoming connections. The multithreaded approach, though probably more efficient, remains the same in essence as the multi-process approach.

Thanks to this, it is possible to serve several clients at the same time. However, this concurrency model doesn’t scale so well. The same code is running in each process (or each thread) but from the OS perspective they are different tasks. Consequently, it all depends on how the operating system (OS) is going to manage multiple tasks at the same time.

Multitasking

In modern OS, multi-tasking is achieved through CPU-time multiplexing also known as time-sharing. Each process is then attributed a given amount of CPU time and can be preempted at some point so the CPU can be given to another process. This is preemptive multitasking, the most common way nowadays of doing time-sharing. A context switch is needed in between two processes: the states of the preempted process must be saved and the states of the process which is going to acquire the CPU must be restored. Though recent operating systems are doing a pretty good job at switching contexts, this is still an expensive operation. Multi-process and multithreaded applications also require a significant amount of memory despite the code between each process/thread is the same. All in all, this model is consuming a lot of resources on the machine, be it CPU or memory.

And it gets worse if the processes need to wait for something.

The problem of wait

There are many occasions on which a process or a thread will have to wait. It will wait for some external events to be completed before they can continue. Such occasions are I/Os. Access to the filesystem or the network are really long operations from the perspective of the CPU. See the numbers from Jeffrey Dean’s talk Stanford CS295 class lecture, Spring, 2007.

| Operation | Latency |

|---|---|

| L1 cache reference | 0.5 ns |

| Branch mispredict | 5 ns |

| L2 cache reference | 7 ns |

| Mutex lock/unlock | 25 ns |

| Main memory reference | 100 ns |

| Compress 1K bytes with Zippy | 3,000 ns |

| Send 2K bytes over 1 Gbps network | 20,000 ns |

| Read 1 MB sequentially from memory | 250,000 ns |

| Round trip within same datacenter | 500,000 ns |

| Disk seek | 10,000,000 ns |

| Read 1 MB sequentially from disk | 20,000,000 ns |

| Send packet CA->Netherlands->CA | 150,000,000 ns |

Blocking I/Os (or synchronous I/Os) will tie up the system resources as the waiting processes/threads cannot be used for something else. And from the CPU perspective, any I/O which is not done from/to memory takes ages. Fortunately the system itself is not stuck while I/Os are happening. The OS is going to preempt (i.e. interrupt) the process waiting for an I/O, allowing the CPU to be used by another process. But this costs another context switch and meanwhile I/O intensive applications will spend most of their time… waiting !

A battle for the CPU

So, the more processes there are, the more they will compete for the CPU. The more I/Os the application is doing, the more context switches there are, amplified by the number of process/threads the application is made of. At some point, no matter how good the operating system is, it is going to become overwhelmed. It will spend most of its time switching contexts and have many processes/threads waiting either for I/O or to acquire the CPU. This basically means that in such a model, the scalability is not at all linear to the number of processes/threads up to the CPU limit. The capacity gain of adding a process/thread significantly decreases with the number of active processes/threads.

Event-driven concurrency model

The alternative is to use an event-driven model. This has proved useful in many products such as nginx for example, the second most popular open-source web-server as of May 2012 or Twisted, a python framework for event driven networking engine or in EventMachine, a ruby framework for event processing. In an event model, everything runs in one process, one thread. Instead of spawning a new process/thread for each connection request, a event is emitted and the appropriate callback for that event is invoked. Once an event is treated, the process is ready to treat another event.

Such a model is particularly interesting if most of the activities can be turned into events. This becomes a really good concurrency and high-performance model when any I/Os (not just network I/O as is the most common in existing frameworks) are events. It is based on event patterns such as the Reactor or the Proactor which are patterns for Concurrent, Parallel, and Distributed Systems; documents from Douglas C. Schmidt. This event-driven concurrency model is superior to the traditional multithreaded/multi-process one: the memory footprint is drastically reduced, the CPU is better used and more clients can be served concurrently out of a single machine.

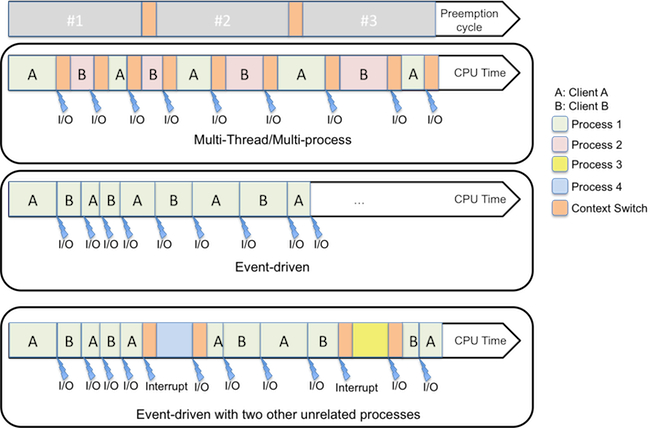

This can be pictured as below (everything is of course greatly simplified compared to what happens in real life):

Multi-Thread/Multi-process figure (See above)

If nothing specific happens, the OS is going to preempt the various tasks at regular intervals (see preemption cycle example picture) in order to give them a chance to equally acquire the CPU depending on the scheduler policy. The OS will however also preempt processes at natural pauses. These pauses can be of different sorts but we will consider only I/O waits here. Since the process is waiting, the CPU can be given to someone else.

Event driven figure (See above)

In a multi-thread/multi-process intensive I/O applications, and assuming there is no other process than the ones serving client A and client B, the OS is doing many context switches and a significant amount of time is spent in switching contexts. In an event-driven model, also assuming there is no other process than the one serving client A and client B, there is no waste of time and the CPU is used at its maximum capacity to serve client A & B.

Event driven figure with two other unrelated processes figure (See above)

In real life, the operating systems always have some other processes running along with the one serving the clients so it looks more like what is pictured in “Event-driven with two other unrelated processes”. However, we can see that the event-driven process is using the maximum of its allocated CPU time.

The event loop

To some extent, one can consider the event-driven approach being very similar to cooperative multitasking but at the application level. Event-driven applications are themselves multiplexing CPU time between clients.

There is obviously a risk with this; the same as with cooperative multitasking in fact. A risk which explains why at the OS level, preemptive multitasking is used. If the process at some point can block for one client, then it will block all the other clients. For example, in cooperative multitasking a non-responding process would make the system hang (Remember Windows before Windows 95 or Mac OS before Mac OS X ? )

In event-driven model, all the events are treated by a gigantic loop known as the event-loop. The event-loop is going to get from a queue the next event to process and will dispatch it to the corresponding handler. Anyone blocking the event-loop will prevent the other events from being processed. So in Node (and in all event-driven framework) the golden rule is “DO NOT BLOCK THE EVENT LOOP”. Everything has to be non-blocking. And Node is particularly good at this because all the API it exposes is non-blocking (with the exception of some file system operations which come in two flavors: asynchronous and synchronous).

And JavaScript in all this ?

JavaScript is a language that was invented in 1995 by Brendan Eich for the Netscape browser. It lived inside the Browser for years. With Web 2.0, JavaScript became very popular among web developers. In Browsers, JavaScript was used to add more features to the HTML interface to make them more friendly and similar to native applications. As such, JavaScript was dealing with events (onclick, onmouseover, etc…) through callbacks. That makes JavaScript extremely well suited to event-driven programming.

But there is more.

JavaScript and I/O

JavaScript also has a specificity: it was designed for being used and ran inside a browser and as such it is missing basic I/O libraries (such as file operations). A language without an I/O library is useless on the server-side. But JavaScript was living inside the browser. It didn’t need to do I/O… until Node.

That’s why, Node conceptors, partly leveraging on emerging initiative such as CommonJS to use JS outside of the browser, added a complete I/O API. And because there was no prior art, they had the ability to make everything non-blocking. Finally, the fact there was no I/O library in JavaScript turned out to be an advantage because it allowed to make I/O natively1 non-blocking in Node. And for disk I/O, this is unusual.

Conclusion

Node has combined an event-driven programming model at its heart and JavaScript as the developer-facing programming language enriched with a set of modules, including a complete non-blocking I/O API. This makes Node a lightweight, easy to use and powerful server-side environment, particularly well suited for I/O bound applications. Node makes it possible to write a complete web application from backend to UI using one single language. For some people, this is considered a serious advantage.

Node has met widespread adoption since it was introduced in 2009 by Ryan Dahl at the JSConf.eu. In 2012, Node was elected InfoWorld’s Technology of the year Award Winner.